New studies highlight deadly antimicrobial resistance outbreaks in Kenya’s neonatal units

- Created by Sande Onyango

- Health & Wellness

New research tracking Klebsiella pneumoniae, a bacterium known to cause severe sepsis in newborns, shows that outbreaks in Kenyan hospitals are frequent and often deadly.

In Kenya’s neonatal wards, where the country’s most fragile patients begin life under medical care, scientists are raising fresh concern about a dangerous hospital‑linked threat, drug‑resistant infections.

New research tracking Klebsiella pneumoniae, a bacterium known to cause severe sepsis in newborns, shows that outbreaks in Kenyan hospitals are frequent and often deadly, underscoring the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in child health.

Klebsiella is already recognised globally as a leading cause of neonatal bloodstream infections. But genomic evidence from Kenya suggests the pathogen is spreading mainly through hospital outbreaks, with high mortality rates among infected babies.

A study led by Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) researcher Dr Anne Amulele analysed clinical and genome sequencing data from neonatal sepsis cases across three hospitals between 2020 and 2023, alongside more than two decades of surveillance data from Kilifi County Hospital.

The findings were stark. Mortality reached 32 per cent in the multi‑hospital NeoBAC study, 41 per cent among neonates in Kilifi, and 56 per cent among infected infants. The researchers concluded that Klebsiella bacteraemia occurred mainly in outbreaks with high mortality, pointing to the vulnerability of newborn units where infections can spread rapidly.

One of the most alarming findings was how often infections were linked to transmission clusters inside neonatal wards. In the NeoBAC study, 81 percent of cases occurred within outbreak clusters, while nearly half of infections in Kilifi neonates were also outbreak‑related.

“These babies spend their first days of life in hospital, and that’s where they’re exposed to pathogens that have become resistant to the antibiotics we rely on,” Dr Amulele told AVDelta News.

“Once they are infected, treatment options are limited, and mortality can be very high. That’s why we’re focusing on prevention through vaccines, while also supporting better hygiene and infection control.”

These patterns suggest that infections are not simply sporadic, but may move through crowded wards, shared equipment, or gaps in infection prevention systems, raising urgent questions about hospital safety for premature and vulnerable babies.

The rise of antimicrobial resistance has turned Klebsiella into one of the most feared hospital pathogens. As resistant strains survive treatment, doctors are left with fewer effective antibiotics, particularly in neonatal care where drug options are limited.

“The more you use a certain drug, you kill off what is sensitive, but you select what is resistant,” Dr Amulele warned.

Public hospitals often rely on affordable first‑line antibiotics, but Klebsiella is increasingly resistant even to these medicines, forcing clinicians to turn to newer drugs that may be costly, unavailable, or unsuitable for newborns.

With treatment options shrinking, researchers are now looking beyond antibiotics toward prevention, including vaccines.

A major peer‑reviewed study published in PLOS Medicine in January mapped Klebsiella diversity across Africa and South Asia, analysing nearly 2,000 isolates from 13 countries. Researchers estimated that a maternal vaccine covering at least 70 per cent of infections could prevent 400,000 neonatal sepsis cases and avert 80,000 deaths annually, most in Africa and South Asia.

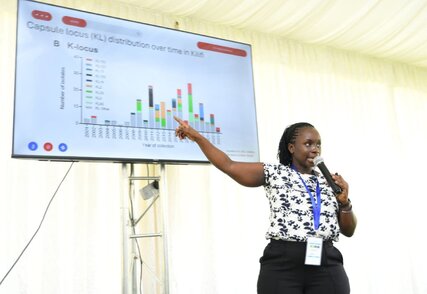

However, vaccine development faces a major hurdle because Klebsiella is genetically diverse. The PLOS Medicine study suggested that a 20‑valent vaccine targeting the most common capsular types could cover about 73 percent of infections across regions. Kenyan genomic surveillance shows an even more complex picture. In Kilifi alone, researchers identified 61 different capsule types, with dominant strains shifting over time.

The recent Kenyan research found that more than 30 K types would likely be needed to cover over 85 per cent of local isolates, raising questions about how future vaccines can remain effective as strains evolve.

Addressing this challenge, Mr Kenneth Mwige, Director General of the Kenya Vision 2030 Delivery Secretariat, said Kenya is determined to strengthen local vaccine capacity and reduce dependence on imports.

“We have realised that health security is national security,” Mr Mwige said.

“Kenya must be self‑reliant in vaccine production so that our people are not left behind during global health emergencies.”

He highlighted the Kenya BioVax Institute as part of this long‑term push, stressing that partnerships between government, research institutions, and industry are key to building a resilient health system.

For Kenya, the findings highlight how AMR is not only a global crisis but an immediate threat in neonatal wards, where infection outbreaks can spread quickly and treatment options are narrowing. Scientists say stronger surveillance, improved infection prevention, and sustained investment in vaccine development will be essential to protect newborns from infections that are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat.